Buy The Fish that Ate the Whale by Rich Cohen

Buy The Fish that Ate the Whale by Rich Cohen

(buying through that link supports Expat Chronicles)

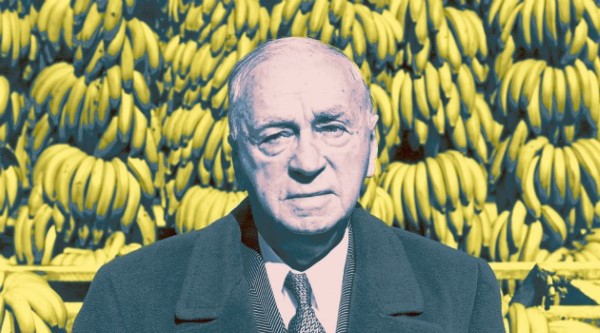

The Fish that Ate the Whale is a biography of Sam Zemurray, a man of many labels: immigrant success story, self-made American, hypercapitalist, domineering gringo, exploitative imperialist, benevolent philanthropist, Zionist. His story is amazing.

Zemurray was a Russian Jew who emigrated to the US in 1901 at the age of 14. He got involved in the banana trade on the docks of New Orleans, unloading “ripes” from boats. He got his hands on a near-rotted inventory and hawked them on the street from a cart. He rose in the industry until he was at the top, founding Cuyamel Fruit Company which was bought out by United Fruit, and then staged a hostile takeover of United Fruit to be the top banana seller in the world.

One theme in Gabriel Garcia Marquez’s One Hundred Years of Solitude (which is quoted often in The Fish that Ate the Whale) is the arrival of the banana gringos, the banana colony of professionals segregated from the locals, and their all-encompassing power culminating in the Banana Massacre.

In 2010 I published Guatemala and United Fruit, about the US-sponsored coup d’etat of Guatemala’s democratically elected leader in 1954. Again, we see banana gringos causing chaos in Latin America. United Fruit changed its name to Chiquita, but didn’t escape scandal. In 2007 Chiquita was fined $25 million for making illegal payments to paramilitaries in Colombia.

So when I heard of this Zemurray biography, I had to buy. Here’s Cohen’s summary of this amazing life:

[Sam Zemurray was] a symbol of the best and worst of the United States: proof that America is the land of opportunity, but also a classic example of the Ugly American, the corporate pirate who treats foreign nations as the backdrop for his adventures.

Cohen on the banana industry:

The original sin of the industry touched everyone: the way the banana men viewed the people and the land of the isthmus as no more than a resource, not very different from the rhizomes, soil, sun, or rain. A source of cheap labor, local color. One definition of evil is to fail to recognize the humanity in the other: to see a person as an object or tool, something to be put to use. The spirit of colonialism infected the trade from the start.

I don’t like to judge men of history by today’s standards. Someday people may call you evil for eating meat or driving a car. You’re a product of your time, as were slave-owners before Christ and the Spanish conquistadors who felt they were bringing Catholicism and civilization to the American savages. It wasn’t a question of morality at that time, as eating meat and driving a car aren’t moral issues today.

It may be difficult to imagine, but the banana industry was much like the present-day oil industry. The companies were extremely powerful with both Washington-based and geopolitical influence. There’s an entire Wikipedia article on the Banana Wars, “a series of occupations, police actions, and interventions involving the United States in Central America and the Caribbean … Between the time of the war with Spain and 1934, the United States conducted military operations and occupations in Panama, Honduras, Nicaragua, Mexico, Haiti, and the Dominican Republic. The series of conflicts ended with the withdrawal of troops from Haiti and President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s Good Neighbor Policy in 1934.”

There were a generation of entrepreneurs exploring the Caribbean and Central America, looking for how to make a banana business work. Zemurray was one of these gringos:

You see him in the cantinas of Omoa, the big Russian in the doorway, buying drinks for everyone. Unlike most banana executives, Zemurray was comfortable with the people of the isthmus. “Sam adapted himself to the ways of life of those he contacted,” Fortune reported. “He cultivated friendship, and did not scorn to take a drink with the peasants. He acquired a wonderful command of their language, including swear words, which he didn’t hesitate to employ. He became a Hondureño.” Zemurray told the locals he would bring them wealth and good jobs. When it came time to hire, he offered a wage ten times the going rate, which angered other employers.

…

Unlike other bosses, Zemurray lived in the jungle with his workers, spoke their language, knew what they wanted and what scared them … It’s why he was hated and why he was loved. Because he was a person and a person you can disagree with and be angry at but still admire, whereas United Fruit was faceless in a way that terrifies. It’s why banana workers rallied to the big Russian as their own hedge against El Pulpo. It’s why some people in Honduras still speak of Samuel Zemurray with rueful affection.

Zemurray wasn’t just mingling with peasants. His main goal was to make connections with power:

He was seeking sweetheart deals that would exempt his company from taxes and duties. Such corrupt understandings were common enough in the business to have a name: concessions, unofficial agreements without which no banana man could succeed. The trade depended on cheap fruit, necessitating cheap labor, cheap land, and no extra fees. The smallest additional cost – a penny per bunch, say – would drive the price above the market rate set by United Fruit. Though the Dávila government was not the most pliable, Zemurray did eventually secure his concessions (by kickback, by bribe). In Honduras, Cuyamel would be exempted from import duties on all equipment, such as freight engines, train tracks, railroad ties, steam shovels, machetes; exempted, too, from paying property, labor, and export tax. Zemurray’s bananas would arrive in the United States unencumbered by such fees – this meant he could sell his product just as cheaply as United Fruit.

Once set up, the gringos would come down to manage the banana operations. They were known as the banana cowboys:

In the first weeks, they lived in tents, then moved into cabins, barracks, and bungalows. They worked from four a.m. till noon, after which it was too hot to linger outdoors. They wore sandals when they worked, shirts opened to the belly, straw hats, and pants with a machete hooked to the waist.

…

Central America was a fantasyland where nostalgic North Americans could live their dream of Western wilderness. There were old hands who had been on the isthmus long before the incorporation of the United Fruit Company, men who had come looking for a personal El Dorado and realized too late they were ruined for any other kind of life. There were managers who came to get their cards punched and planned to stay no more than a season or two but got stuck. There were rowdies who had come on a spree, to dress in khaki and carry a gun. There were college men who came for the job but stayed for the stuff, how far the dollar could go, a life of leisure, servants, and clubs. Unifruco, the United Fruit magazine, which was as slick as The New Yorker, speaks of company men returning to an earlier stage of American history on the isthmus, of living as men used to live before the women took over and softened us with their rules and finery, of confronting nature in the spirit of Davy Crockett or Daniel Boone, of again seeing the forest as primeval, wild, and mysterious.

…

Honduras, Guatemala, Costa Rica, Mexico, Colombia, Ecuador – no matter the country, the scene was always the same. The grid of streets, houses and stores, the electrified fences, golf courses, banana fields, bowling alleys, and swimming pools … gin and tonics and Dewar’s White label Scotch on tropical verandas; endless miles of private jungle fiefdoms, natives who were variously brooding, surly or submissive; boots, khaki uniforms, horses and pistols … the early morning produce markets and the colorful, crude men who ran them: longshoremen, traders, plantation managers, ambitious men, hard men, lazy men, rich men; and behind it all a tradition of enormous wealth and power and privilege … By 1940, the network of banana colonies had developed its own society, its own codes, poets, heroes. There was cruelty and racism, the dark-skinned made to scrape and bow, the white man king (the constant mention of skin color, defined to the minutest degree, is perhaps the most miserable relic of that era). There was the sporting life, baseball stars who played for U.F. teams in Ecuador and Cuba, who barnstormed, packing the wooden bleachers.

The cultural exchange from banana cowboys is a major reason why baseball dominates many Caribbean countries, and why so many of Major Leage Baseball’s best players today hail from the Caribbean.

These conditions are what coined the term, banana republic, “a politically unstable country that economically depends upon the exports of a limited resource (fruits, minerals), and usually features a society composed of stratified social classes, such as a great, impoverished working class and a ruling plutocracy, composed of the elites of business, politics, and the military.”

Zemurray was credited with the quote: “A mule costs more than a deputy.” Here’s Cohen on that quote:

Though Zemurray denied speaking these words … Are these words evil, or are they a simple statement of fact?

If a man wanted to do business in Nicaragua, there were certain things he had to buy – these included banana mules and police deputies. When balancing the books, you could not miss the fact: a mule did indeed cost more than a deputy.

The book starts with Zemurray’s craziest story, his privately sponsored coup in Honduras. Long before Zemurray had scored concessions from Závila, Honduras paid far too much for a railroad project that was never finished (Tegucilgalpa still has no train service). The government owed $100 million to British bondholders. This concerned American leaders, given the Monroe Doctrine of preventing European powers from invading or occupying any nation in the Western Hemisphere.

The US government enlisted the help of famous banker, JP Morgan, to help the Honduran government. He bought all the outstanding railroad bonds, satisfying British banks. Then he was going to refinance, issuing $5 million in new loans to Honduras on one condition: JP Morgan bankers would have a seat at the Honduras customs office in Puerto Cortés and collect a duty on all imports. The terms, unpopular among Hondurans, were ratified by the Honduran Congress.

With JP Morgan bankers at the port, Zemurray couldn’t import all the equipment he needed to build his business tax-free.

[S]o that set up Zemurray’s leading a revolution to get Davila’s government replaced with someone who would honor his concessions. They picked General Manuel Bonilla, who was deposed in a 1907 coup and exiled to New Orleans. “[H]e was dark skinned and broad nosed, features described by diplomats as Indian in a way that would give the operation the aura of popular revolt.”

Zemurray hired a gang of gringo mercenaries who had fought wars in Central America and formed an expat community in the New Orleans French Quarter. The title of the chapter is ‘Revolutin’ (as in, “Let’s go ‘revolutin’!”), a term coined by soldier of fortune Lee Christmas.

The band of mercenaries set off with the deposed General to overthrow the Honduran government with weapons bought by Zemurray. Once in the region, the gringos got all drunk the night before a morning raid on a key fort. Too eager to wait till morning, they stormed the station at 4 AM drunk, and succeeded.

As rebels celebrated the conquest, the captain of the Hornet sat on deck with a man named Florian Davadi. Papers were signed, and everyone shook hands. Having promised to pay $40,000, Davadi had become the owner of the Hornet. As the property of a citizen and current resident of Honduras, the ship could take part in the war without violating the U.S. Neutrality Act.

…

Less than two weeks later, the ship was seized by the U.S. gunboat Tacoma for violating the U.S. Neutrality Act. After dismissing Bonilla’s protest regarding ownership, the navy towed the Hornet to New Orleans to be held as evidence in a criminal investigation. In a strange way, the seizure, which would have been helpful to President Dávila a week earlier, hurt him now. Having established a base in Trujillo, the insurgents no longer needed the Hornet. But its seizure made it look to Hondurans like the United States was intervening in a civil war on the side of the government. It was a feat of propaganda: Bonilla and Christmas, working with Zemurray, were able to frame the war as an insurgency, the people rising up against a government selling the nation to gringos and Yankee bankers, whereas what you really had was more sinister and interesting – a battle waged by a private American citizen, a corporate chief, against a debt-ridden but sovereign nation.

The government fell on the condition Bonilla wouldn’t be president, but he was elected by a landslide in the first election.

“Bonilla did not forget his benefactor,” reported Life. “One of his first official acts was to have congress give Zemurray concessions covering the next 25 years.”

Zemurray’s settlement included permission to import any and all equipment duty-free; to build any and all railroads, highways, and other infrastructure he might need; a $500,000 loan to repay “all expenses incurred while funding the revolution”; as well as an additional 24,700 acres on the north coast of Honduras to be claimed at a later date. No taxes, no duties, free land – these were the conditions that would let Sam Zemurray take on United Fruit.

…

As for the issue that caused the war in the first place: Zemurray tried to refinance the national debt of Honduras himself, working with banks in New Orleans and Mobile to buy out British bondholders. In the end, he was able to chip away at the fringes, but the bulk remained and grew, accumulating interest. As of 1926, Honduras still owed $135 million on the railroad that went nowhere.

Then the book tells the story behind the top conspiracy theory surrounding Sam Zemurray: that he authored the assassination of an American governor. Sam Zemurray’s hometown was New Orleans, and with the Great Depression came the emergence of a populist liberal in Louisiana, Huey Long AKA Kingfish. Zemurray was a New Deal Democrat and supporter of FDR, but Long was a different kind of Democrat altogether, more similar to Hugo Chavez or Evo Morales. Zemurray was the epitome of a capitalist, and the top politician in his back yard was Hugo Chavez. New Orleans is an important city in American history, but it’s a small city in a small state. It was just a matter of time before these juggernauts bumped heads. When Long was killed, there were circumstances that pointed at Zemurray, but Cohen largely dismisses them as heresy, adding that all the big business leaders in New Orleans spoke openly about assassinating Long.

After the Kingfish episode, Cohen tells of a different kind of banana war – one between banana companies – when Cuyamel territory expanded to the Honduras/Guatemala border, where the Utila river separated them from United Fruit’s land:

The struggle commenced as a war of pranks, with each company taunting and testing its rival. Agents from United Fruit crossed the river at night, cut water lines, tipped over trucks, ripped up train rails. Zemurray sent his own team of brigands across the Utila to retaliate. These were the last of the roughnecks who had wandered away from Texas, riding south as the frontier closed, a brooding tribe out of time, each with a horse and pistola, working for next to nothing. I want here to sing an ode to the banana cowboy, that wild, unshaven, hell-raising fighter of yore, terror of the isthmus, hired guy in time of conflict, filibuster in time of revolution, arrived from the streets of New Orleans and San Francisco and Galveston, no good for decent society, spitting tobacco juice and humping extra shells in his saddlebag. These roughnecks found a benefactor in Zemurray, who rode and drank with them. When the Banana War came, they were his avant-garde, crossing the frontier at night, raising hell in the fields.

By this time, the new Honduran president favored United Fruit and refused Cuyamel permission to build an important bridge. Zemurray coped with temporary solutions, but he didn’t just cope.

How did Zemurray respond? By making room in his southbound banana ships, not for produce or seed but for hardware, guns, and bullets that found their way to the liberal insurgents who had taken to the hills in Honduras. It was always an option: if the leader is in the pocket of the other guy, change the leader. The State Department, then run by Frank B. Kellogg, received reports of smuggled weapons. A Cuyamel boat, anchored at a Hudson River pier in New York, was searched by the Port Authority. Fifty thousand dollars’ worth of weapons were found.

The Banana War between Cuyamel and United Fruit continued to escalate.

At the last possible moment, the diplomats got involved and a sort of peace conference was convened. In normal cases, this would be the head of the League of Nations calling the presidents of the feuding countries to Vienna or Yalta. In this case, it was officials from the U.S. State Department summoning the bosses of the fruit companies to Washington, D.C. The Banana War threatened American interests, breeding hatred for the United States on the isthmus and posing a danger to a region that included the Panama Canal.

The State Department pressured the companies to merge, despite its creating a monopoly, to end the Banana War. Zemurray sold Cuyamel’s business to United Fruit and retired a rich man. But as the Great Depression raged on, United Fruit’s business declined and Zemurray’s wealth collapsed.

Zemurray had remained an advisor to the company, but the United Fruit management looked down on him as the obnoxious Jew, the cart-pushing immigrant, the pain in the ass. He was ignored.

“I realized that the greatest mistake the United Fruit management had made was to assume it could run its activities in many tropical countries from an office on the 10th floor of a Boston office building,” Zemurray told Fortune.

Zemurray decided to get active again. He studied the business, visiting ship captains and banana field managers to learn why operations were suffering. He visited shareholders across the country to plead his case, that the top United Fruit managers were fucking it all up and only his ideas could restore the company to profitability. He won the necessary votes and spoke his mind at the next board meeting. In an unforgettable scene, the top executive (of what I imagine a 100% WASP, New England elite, Ivy League MBA junta of snobs) responds that he didn’t understand a word the Russian said, to stifled laughter. Zemurray showed him his proxies and shouted, “You’re fired! Understand that?”

That’s how Zemurray took control of the much larger United Fruit in a boardroom coup that inspired the title, The Fish that Ate the Whale. He went back to work as a banana gringo and slowly restored the company to profitability and growth. Struggling to survive the Great Depression, World War II started.

All shipments to Britain and its colonies were banned. One day, the British market accounted for 20 percent of United Fruit’s profits; the next day, it was gone … Soon after the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor, the American War Department followed the British example, limiting the importation of bananas (a quota) and seizing most of the Great White Fleet. (The company was left with only the clunkers.)

Zemurray overhauled his business model to survive, making rubber, quinine, and other products that helped the war effort. His son, an Air Force pilot, was killed in North Africa, a defining moment for him. Hitler’s extermination of Jews also affected him.

On Zemurray’s Jewishness:

Zemurray did not have a strong sense of Jewish identity. It was never how he described himself … The fact that neither of his children married Jews, raised Jewish children, or much cared about Jewish causes tells you that Sam did not dwell on the subject at home, obsess, or fill his children with fear of goyim. When offered the freedom of America, which is not only freedom here and now, but also freedom from the past, freedom to choose what to remember, he grabbed it.

And yet, like more than a few such men – European-born Jews who shrugged off ethnic identity as soon as they touched American soil – Zemurray became, in late middle age, a champion of Zionism.

The Holocaust changed everything:

It’s hard to explain the effect of the Holocaust on men like Sam Zemurray. Self-made Americans who had always felt secure in their adopted country, they were suddenly reminded, in the middle of life, of the true nature of their condition. No matter his wealth or power, the Hebrew would always be a stranger in a strange land …

What’s more, as the details emerged – six million – men like Zemurray came to regard themselves as all that remained of a lost world. The Jews of Europe had been a remnant of an ancient kingdom. The Jews of America were thus a remnant of a remnant, invested with special responsibility. It’s up to us to see it never happens again was the sentiment of the moment. For many, the only solution was the creation of a Jewish state. Not only would it protect the living, providing shelter and a place of refuge, it would redeem the millions who had died.

…

After the war Zemurray was contacted by Zionist activist Ze’ev Schind, who was smuggling Jews out of Europe and into the newly created state of Israel, defying Britain’s maximum 75,000 immigrants per year under the White Paper of 1939. Schind asked for Zemurray’s help.

Contacts established, money raised, ships purchased, papers issued – documents that caused the harbormaster to sign the manifest and open the gates. Zionist agents spirited refugees out of the DP camps, leading them over mountain trails to ports in Romania, France, Italy, where ships waited at anchor. Some of these tubs, jammed with poor lost souls, made it through the blockade. Others were stopped by the Royal Navy, boarded, turned back.

…

The British Mandate of Palestine was terminated in May 1948. According to The Jews’ Secret Fleet by Joseph Hochstein and Murray Greenfield, the Bricha had by then carried thirty-seven thousand Jewish refugees to Palestine – many of them on American ships procured or sped along by Sam Zemurray.

…

With the coming end of the British occupation, the fate of such a state had been turned over to the United Nations, where it would be decided by a vote in the General Assembly. The resolution to divide Palestine into two nations – one Arab, one Jew – needed a two-thirds majority to pass. A season of politicking would begin as soon as that vote was scheduled, a game Zemurray was uniquely positioned to play.

…

Sam Zemurray went to work, calling key players in banana land, wheeling, cajoling, strong-arming. It was the culmination of his career, the hour when Zemurray could finally use everything he had learned to play a secretly decisive role on the world stage … Zemurray told Weizmann that every vote from Mexico to Colombia was for sale, but the price was often prohibitively high … The ensuing bribing and lobbying became so intense that President Harry Truman complained to Weizmann of hardball tactics: Truman found it “unbecoming.”

…

By the time of the final vote tally, enough countries had changed their vote – Haiti from no to abstain; Nicaragua from abstain to yes – to pass Resolution 181. Knowing about the work of Zemurray, certain yes votes that might otherwise seem mysterious – Costa Rica, Guatemala, Ecuador, Panama – suddenly make perfect sense. Behind them, behind the creation of the Jewish state, was the Gringo pushing his cart piled high with stinking ripes.

But of course it wasn’t over. As soon as they were independent, Israel faced regional hostility and the eruption of war from all sides: Egypt, Jordan, Syria, Iraq, and Lebanon. First world countries declared an arms embargo on the region and, being a brand new nation, Israel had no weapons to defend itself.

You name it, they did not have enough: bullets, rifles, pistols, grenades, trucks, tanks … Israel survived on the smuggled weapon, the clandestine arrival, the box hidden behind the false panel on the container ship – it says vegetables, but it smells like gunpowder. In the first days of the war, the majority of these boxes came from only three places, sent by three types of interested parties: Czechoslovakia, where Communists shipped trucks, guns, and planes with the consent of the Soviets, who believed a prolonged Middle Eastern conflict would embarrass the British; New York and New Jersey, where, at the urging of Meyer Lansky and Longy Zwillman, dock bosses like Socks Lanza looked the other way as ships bound for Hiafa or Tel Aviv were filled with weapons; and Central America, where banana men filled ship after ship with boxes marked FOOD or SUPPLIES, carried weapons to the Israeli Defense Force.

Much help came from Anastasio Somoza García, known as “Tacho,” who ruled Nicaragua from 1936 until 1956, when he was assassinated. According to Ignacio Klich, Somoza smuggled weapons to Israel throughout the 1948 war. Years later, when world opinion turned against Somoza’s grandson Tachito, who ruled Nicaragua from 1967 until he was assassinated in 1980, only Israel continued to ship arms to the dictator. When asked about this, Prime Minister Menachem Begin spoke of an old debt that needed to be honored.

Latin America changed after World War II.

Asked to name a hero, most South American liberals of that era would mention FDR, specifically citing his four freedoms: freedom of expression, freedom of worship, freedom from want, freedom from fear. In short, the Central Americans heard our words and actually believed them …

The call of increased rights and freedoms was a challenge to United Fruit, which depended on compliant governments and cheap labor. What’s more, with the start of the cold war, the struggle on the isthmus got tangled up with the global battle between capitalism and communism, which turned even the smallest feud into a test of ideologies …

One of Zemurray’s tactics in surviving the Depression was to devalue land holdings to reduce tax burden, which was legitimately worth less at that time. The undervaluation mentioned in my earlier Guatemala coup piece was particularly incriminating, but Cohen put it into context. Another incriminating detail was how much land United Fruit left fallow, but the book explains that buying up as much land as possible was Zemurray’s hedge against the havoc-wreaking Panama Disease.

Still, those two facts didn’t help Zemurray’s cause when the Guatemalan Revolution arrived. A major demonstration – demanding their dictator step down, a social security system, decent wages, etc. – turned into a riot that killed hundreds in Guatemala City. It forced Jorge Ubico from power, and his military successor called for elections. At the time:

[United Fruit] owned 70 percent of all private land in Guatemala, controlled 75 percent of all trade, and owned most of the roads, power stations and phone lines, the only Pacific seaport, and every mile of railroad.

…

Juan Arévalo won the presidency with 85 percent of the vote, the first popularly elected leader in the history of Guatemala … His inaugural address promised a new age. He had three audiences in mind: Guatemalans, the government of the United States, and the president of United Fruit. He spoke of his past – a childhood of poverty. He spoke of the future – a vision of big landowners forced to reform and share. And he spoke of his heroes, Abraham Lincoln and Franklin Roosevelt, who “taught us there is no need to cancel the concept of freedom in the democratic system in order to breathe into it a socialist spirit.” He said he would govern by a philosophy of his own invention, which he called “spiritual socialism.”

…

Arévalo, a smart man who understood the limits of his power, was exceedingly careful in dealing with United Fruit. Though he passed land form legislation, he left it unenforced. He focused instead on crowd-pleasing issues that Zemurray could hardly oppose. A forty-hour workweek, social security guarantees, rights of the unions to organize – all based on the New Deal legislation that Zemurray himself had championed in the United States.

…

In 1951, Arévalo was succeeded by his vice president, Jacobo Arbenz …

Arbenz was a different sort of president than his predecessor. Arévalo condemned United Fruit but never undermined the company or challenged Zemurray directly. He was cautious, deliberate. Arbenz advanced soldier-style, by quick, decisive strokes. He was a man aware of time, who wanted to push through his program before the weather changed. He did not fear Zemurray. In fact, it seemed he wanted to infuriate the bosses of United Fruit, make a display of his independence and defiance. He wanted to remind the banana moguls who the elected leader of the country really was. In his inaugural speech, Arbenz promised to make Guatemala “a dependent nation with a semi-colonial economy, [into] an economically independent country.” He said achieving this would mean ridding the nation of the latifundios, large private estates and farms, once and for all.

Arbenz nationalized much of United Fruit’s fallow land, paying them the amount of their official, devalued appraisal from the Great Depression.

United Fruit officials complained to the Guatemalan government and to the U.S. State Department. Even if the seizure were legal, the price seemed grossly unfair. Auditors valued the land at $16 million. The Guatemalans said their appraisal had been determined by the company itself – from its own tax filings … When a formal complaint was filed in Guatemala City – it said undervaluing for tax purposes was an accepted practice understood by previous governments and irrelevant to the land’s actual worth; it demanded full payment of the property’s real value – this came not from United Fruit but from the U.S. State Department, a detail Arbenz should have noticed.

Arbenz rejected the complaint and carried on as if no one could stop him … By defying El Pulpo, Arbenz became a liberal hero across Latin America … It marked the dawn of a new revolutionary era in the South. Spanish-speaking reformers of every variety – Communists, Socialists, Trotskyites – as well as adventure seekers and people simply curious to taste freedom, set off for Guatemala. By becoming a symbol and a refuge for the disenchanted, the country drew still more attention from the State Department. In the minds of diplomats, Guatemala was turning into a rogues gallery … All the rabble-rousers who would long bedevil the United States seemed to be in Guatemala City, or on their way [including a young Che Guevara].

Impossible to justify or even pull off a “popular revolution,” Zemurray went to work on the American side. He hired an infamous PR specialist to manipulate public opinion. They portrayed Arbenz as a Communist to key opinion leaders in America.

Never mind that Arbenz claimed no allegiance to the Communist Party; never mind that Arbenz cited Franklin Roosevelt as among his heroes; never mind that many of the Arbenz policies that United Fruit found so offensive were patterned on the New Deal – the signs were evident for those who knew where to look.

…

The situation on the isthmus, unheard of a few months before, moved onto the national agenda, where it was described not as a threat to a corporate interest, nor as a threat to the region, but as a threat to the American way of life.

A Guatemalan coup was planned.

Some experts consider Zemurray’s overthrow of the Honduran government a model for almost all the CIA missions that followed. In 1911, Sam deployed many tactics that would become standard procedure for clandestine operations: the hired guerrilla band, the phony popular leader, the subterfuge that convinces the elected politician he is surrounded when there are really no more than a few hundred guys out there.

…

Eisenhower gave the go-ahead for Guatemala in August 1953, at a meeting of something called the 10/2 Committee. Operation Success would replace the Arbenz government, defeating communism on the isthmus …

…

The CIA eventually selected Carlos Castillo Armas, a thirty-nine-year-old disaffected officer in the Guatemalan military living in exile in Honduras. Because he agreed to all the conditions and because … he “had that Indian look …, which was great for the people.”

…

[Castillo Armas] was flown to Florida, then driven to a CIA base in the palmetto grove, where he sat with the clean-cut young men running Operation Success. The outlines of the plan were explained: Castillo Armas would be placed at the head of a liberation movement invented by the CIA, given $3 million in cash, guns, grenades, and, at the right time, technical and air support. If he needed more guns, these would come from the United Fruit Company. Castillo Armas would train his army on island bases in Lake Managua, Nicaragua. A handful of American pilots were meanwhile stationed in Puerto Cabezas, Nicaragua, the same strip later used during the Bay of Pigs invasion. CIA operatives were scattered among a dozen locations, in camps and safe houses, where they prepared the psychological tricks crucial to Operation Success. Exiled Guatemalan newspapermen wrote fake stories that warned of the swelling ranks of the rebel army; printers made up flyers to be dropped from airplanes in the first hours of the war; engineers recorded sound effects – Hunt called them “terror broadcasts” – to be played during the invasion. Panicked newsmen, terrified crowds, exploding bombs – the same sort of tricks Orson Welles used during his War of the Worlds radio drama.

…

It began with a couple of Second World War fighter props piloted by retired air force men flying low and loud, dropping smoke bombs and paper flyers (GET OUT!) on Guatemala City. This was followed by strafing runs, bombs. If you saw three planes in the sky, you were seeing the entire rebel air force. Then came the psychological tricks meant to confuse the people and terrify Arbenz and his loyalists. Hidden speakers boomed out the sound of guns and shells. Fake newscasts filled the entire bandwidth, some calling for the overthrow of the dictator, some claiming the dictator had already been overthrown. Others heralded the arrival of Castillo Armas and his men in the capital, where they were being greeted by jubilant crowds.

…

Castillo Armas, having mustered his army on a U.F. banana plantation in Honduras, marched across the border into Guatemala. His soldiers and weapons were carried on U.F. trains and U.F. boats. He met little resistance. It was less a war than a walk in the country, afternoons of daisy picking, a parade in the mountains. Guatemala 1954 would be the last of the easy overthrows. Because peasants did not want war, because the government believed it could not win, because Arbenz was willing to go farther than anyone had gone but was still not willing to go all the way.

…

On June 27, 1954, [Arbenz] addressed his people for the last time. “For fifteen days a cruel war against Guatemala has been under way,” he said on the radio. “The United Fruit Company, in collaboration with the governing circles of the United States, is responsible for what is happening to us.”

He resigned as soon as he got off the air, turned control of the government over to General Carlos Díaz, crossed the street to the Mexican embassy, and asked for asylum. By that time, Castillo Armas was on the outskirts of Guatemala City.

…

Castillo Armas fulfilled his part of the bargain soon after he secured power. His soldiers tracked down and arrested or killed the military officers and politicians who championed the Guatemalan Revolution. He rounded up or chased away the ideological vagabonds who streamed into the country in the days of delirium that followed Decree 900. He had soon established a police state, imposing the sort of lockdown that would make the rise of another Arbenz impossible. He abolished political parties and trade unions, closed newspapers and banned books he considered dangerous, including the collected works of Fyodor Dostoyevsky and Victor Hugo. He took care of the fruit company, stripping U.F. workers of their right to bargain collectively and shuttering the Banana Workers Federation. Seven of the labor organizers who had been attempting to unionize the banana field hands – there were scores of them; they gave the plantation managers fits – were found dead in Guatemala City. By 1955, the hundreds of thousands of acres seized from the company had been returned.

Five days after the Guatemala coup, the Justice Department sued United Fruit for violating antitrust laws, despite their having pressured Zemurray into merging with United Fruit two decades prior. The image of United Fruit deteriorated. It came to be seen as Halliburton is today: a company with too much power and influence that is hurting long-term American interests in foreign regions. By that time, Zemurray was an old man. He’d already led an amazing life, and had nothing left to do.

On Zemurray’s charity:

Among the highest forms of tzedakah is to give anonymously, in a way that does not disgrace the person in need. Whenever possible, Sam gave without affixing his signature: neither press conference nor public announcement nor strings attached. A private man who shunned publicity, he believed charity was sacred but that those things that often surround it – newspaper pomp, ribbon cutting – were tawdry. I don’t know whether Zemurray read the Bible or knew the code, only that he’d clearly been affected by the folk wisdom, what his father told his mother over the dinner table in Russia: that giving with display is not giving, but trading. I give you money, you give me prestige. Philanthropy that does not degrade is done so quietly not even the rescued learns the name of his rescuer. For this reason, we’ll never know how much Zemurray gave, or to whom. Life said, “Zemurray has given millions for philanthropic purposes – usually in secrecy.” We know of only the public projects and causes, those that could not be advanced without drawing a crowd.

…

Zemurray gave money to establish a clinic for troubled children in New Orleans, funded the city’s first hospital for “Negro” women, and, at the urging of his daughter, made a $250,000 gift to Radcliffe College to endow a professorship at Harvard, an endowment that resulted in the first woman professor on the Arts and Sciences Faculty of the university … He gave vast amounts to The Nation magazine, which had fallen on hard times, and more to found the Zamorano, the Panamerican Agricultural School, which is a short drive from Tegucigalpa. Still considered among the best schools of its kind in Central America, the Zamorano was tuition free. Graduates were discouraged from taking jobs in the banana industry. Zemurray wanted to build an educated Central American class independent of the trade; the overreliance of the people on the fruit companies had become a problem for everyone. he had passion for giving money on the isthmus. His charity in Central America included hospitals, highways, power grids, seawalls, levees, orphanages, and schools. There was a saying in New Orleans: “If you want something from Sam Zemurray, ask for it in Spanish.”

Cohen’s summary on Zemurray’s life:

[Zemurray] started as a kid, a set of eyes peering from the steerage deck of an Atlantic steamer. He grew into a young man, a go-getter hauling ripes. He became a hustler, hurrying through the streets of the French Quarter with a pocketfull of bills. When he went to the isthmus, he became the Gringo humping over the mountains on a mule, buying and clearing swaths of jungle. Then he was El Amigo, the father of the revolution, a man with nothing to lose. Then he was the little guy at war with the Octopus. Then he was a millionaire, a sellout, a retiree, a battler in a political war, a symbol of everything good an bad about America, the opportunity to rise and the inevitable corruption, the best and worst. He had finally become the boss, the kind, one of the most powerful men in America.

…

Perhaps [Zemurray]’s best understood as a last player in the drama of Manifest Destiny, a man who lived as if the wild places of the hemisphere were his for the taking. It was in this spirit that he built his company into a colossus, so big its size became the most important fact of life on the isthmus. The United Fruit Company’s dominance in Central America made a mockery of regional governments, and was humiliating and infantilizing in ways that were hardly understood at the time … Those who lived in the banana lands were ruled not by foreign nationals bringing “civilization” and the word of God but by businessmen who looked on their fields with a cold moneymaking precision.

Sam Zemurray lived one of the greatest lives in history. This article’s been such a monster because the story’s such a monster, and it still doesn’t do the book justice. I had to nix a lot of great content, reduce the Huey Long and boardroom coup stories to a paragraph, the Panama Disease epidemic to a brief mention, and completely omit banana economics, geopolitical implications, and the anti-Semitism. So read the book!

Buy The Fish that Ate the Whale by Rich Cohen

(buying through that link supports Expat Chronicles)

BTW, I learned of this book from Ryan Holiday’s recommended reading newsletter, which I highly recommend for avid readers. I choose at least one book from each edition.

In general, when gringos negotiate/trade with latinos, they prevail. It has been happening this way since the first American traders found their way from Missouri to Santa Fe or the anglo settlers who who were invited into Texas and later revolted. This pattern will always be repeated as the USA expands trade into Latin America.

LikeLike

Colin, you need to find this book: Confessions of an “Economic Hitman” by John Perkins.

LikeLike

@ Mark – I’d heard of it. Ignored by The Economist, WSJ, and FT. The only serious paper to review it was the NY Times Travel section, and they poked light fun at it. http://travel.nytimes.com/2006/02/19/business/yourmoney/19confess.html?pagewanted=all&_r=0

This was all I needed to hear from that review: “Mr. Perkins’s coup has been to overlay a dry, mainstream notion — that American companies and multinational institutions were less than discriminate in lending to third-world nations — with sex, confession and fiery plane crashes.”

Interesting about this book, the Sam Zemurray story, is that some people see the evils of capitalism, some see the evils of the United States of America, and some (me) just think it’s COOL.

LikeLike

Things to google: Wiliam Walker, Blackwater Colombia, Airscan Colombia, Sir Henry Morgan.

Mercenaries and pirates.

LikeLike

Wanted to let you know I read all this the other day but didnt get to comment. Fascinating stuff, to be sure. It would have been a hell of a time to be alive, and to be in the mix with dealings like that.

Makes for a hell of a story, and being a storyteller, story is king.

LikeLike

First class read. An interesting story well told.

LikeLike

The book sounds like a truly great read, and this is a great article too.

A book addressing these business wars is Smedley Butler’s “War is a Racket”

LikeLike

To nitpick a point: the conquistadors brought the opposite of civilization. They stole, plundered and killed from an already existing civilization. They did this out of pure greed and dogmatic ignorance.

They burnt the libraries of already existing civilizations to ensure THEIR God stood alone unopposed in the eyes of history.

I don’t believe Spanish reports about “human sacrifices” just as I would be unlikely to believe what a Nazi says about Jews.

LikeLike

But to be fair I find your posts educational and I’ve been reading a fuck of a lot of them lately 🙂

LikeLike

Thanks for sharing your thoughts about Pirates of the carribean hack tool.

Regards

LikeLike