There are two schools of thought about having friends in Latin America. Maybe there are more, but a large contingent of gringo expats believe you can’t have true friends in native Latin Americans.

I am unsure. I am skeptical it’s impossible, but I’ve heard it so many times, with such insistence, from experienced expats, that it’s hard to dismiss. I’ve never had a close, native friend who I would, say, loan $1000 to.

Even my Peruvian wife insists it’s impossible. Take that with a grain of salt, because she would be delighted if I had no friends of any kind, and spent all my time with the family. But she regularly insists that I not trust Peruvians (or any other Latin American nationalities), whether they’re friends or not. There is a real cynicism beneath the warm friendliness in Latin American culture.

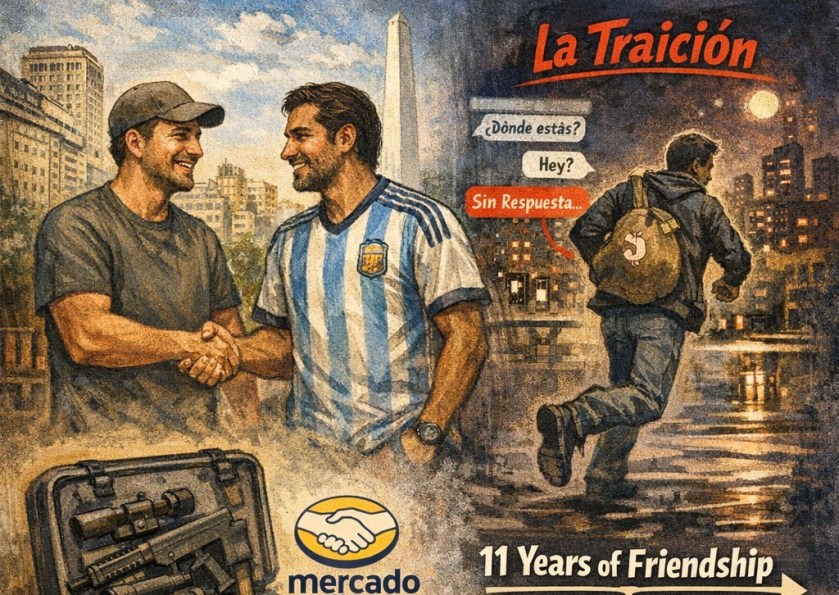

One friend who believes friends are impossible was ripped off in a remarkable way. He had a close Argentine friend in Buenos Aires for 11 years. For most of that time, they operated a small business together. My friend would bring gun accessories unavailable in Argentina — hard-to-find accessories that Argentina doesn’t produce, the market doesn’t justify big players importing and protectionism prevents small players from getting in at scale. So like many industries across the region, and the world I imagine, these niche products walk in via suitcases by reverse mules and get sold online in small batches.

My friend would bring bump stocks, night scopes or whatever in suitcases when he came in from the United States. He would give the merchandise to his friend, who would sell it on MercadoLibre. Once sold, he reimbursed my friend for the cost of the product and they split the profits.

This worked for years … until it didn’t. After 11 years of friendship, and who knows how many transactions, the Argie received a delivery of merchandise and vanished. He didn’t respond to calls, texts or emails. My friend estimates the debt he was owed at $250. The Argie threw away 11 years of friendship for $250.

That is what’s remarkable to me: 11 years of goodwill for $250. And stories like this are abound.

Reading old accounts from the Mexican-American War, I couldn’t help noticing how many times the American soldiers described the Mexican people as “treacherous.” That word comes up repeatedly.

This is why some gringo expats say you can’t have a close Latin American friend. They’ll betray you someday. Whether it’s for money, a girl or whatever, they will betray you.

I have never been betrayed, but I never got too close to anybody. Looking back, my closest Latin friends were the deported Colombians, and they weren’t culturally Colombian. They were raised in the U.S., agringados.

In Lima I was part of a good group of Peruvian dads whose children were friends. These guys are still friends, and one family in particular grew close to ours. I would consider that father a close friend. He was there for me in a jam once (I didn’t need money, however).

But would we be friends if our children weren’t friends? If I were to loan him $250, would he pay me back? On a long enough timeline, would I get burned? I don’t know.

I tried to think of a native (not agringados) friend who didn’t have children. Gustavo in Colombia came to mind, and I don’t doubt for a second he would have betrayed me someday. For money, for a girl. Or maybe for both at the same time. He’s still fun and I’d hang out with him today, even though I don’t snort coke anymore, or drink for that matter. But I wouldn’t say I ever trusted him.

I was on a basketball team during my first year in Arequipa. If I were the type to fit in (which I’m not), and I made Arequipa my home and devoted a good part of my life to that team and that parish, I could see myself having a couple lifelong friends from that group of guys. And I believe they were trustworthy. But I don’t fit in. Never have, probably never will.

And that is one major reason why expats might not have natives as close friends. You have to adopt the culture as your own and invest A LOT of time. You have to burn your ships behind you to have that kind of connection. If you’re keeping one foot in the United States via remote work, or your attention on your native culture, you’re not fully in the pool. To fit in, you have to jump in the deep end with no life preserver.

Latin America is still a parochial society, even as it grows less religious like the rest of the world. Men are usually friends for the rest of their lives with their friends from primary school. They may make casual friends and acquaintances later, but their true friends are the boys they grew up with in the parish. If you’re not in that group, then you’re out. And you always will be.

My father-in-law says he has “amigos” and “compañeros” – friends and companions. The vast majority of what I would call his “drinking buddies” are only “companions” in his eyes. To graduate to “friend” takes decades. It probably doesn’t happen anymore. His true “friends” were from childhood or the police academy. Not any policeman, but specifically the ones he went through the academy with. Regardless of rank today, they are still close.

Even a Peruvian or Chilean who is not Catholic still grew up in what is effectively a parish. His primary school pals would have all had in common not being Catholic. Or growing up under parents who went out of their way to send them to a secular school. That creates a close bond, like a parish, and they are still friends today too.

Not many gringos are going down to South America at 16 or 18 years old. Most expats skew older. I left at 29. Your friendships are mostly crystallized by then. It’s time to move on, shift your focus. Middle age is about family and money. Even after repatting back to St. Louis, where I grew up and went to college, I only saw friends once in a blue moon. Some I never saw before moving to Philly.

It took me a while to learn that because we expats are a little growth-stunted. Most of us left home because we didn’t want to grow up. We arrived in Latin America and started partying. No regrets, no old faces to judge us or compare ourselves with. You can lose years in that whirlwind and not mature much. You can create close friendships with other gringo expats, living a shared experience of trying not to grow up in Latin America.

For a long time I thought joining a fraternity in college was a waste of time. If I could do it all over again, I thought I wouldn’t. I’d just make friends organically. But it’s hard to ignore how many of those guys I’m still in touch with. And when we get together every 10 years or so, how we pick up right where we left off. It’s like nothing changed.

Those shared experiences are required for the kind of lifelong friends I’m talking about here, and they probably have to be shared in relative youth.

If you’re trying to recreate that in Latin America with natives, you can’t keep one foot on dry land. You have to jump in. You have to get in where you fit in. If not, you can run around with the gringo expats and make great friends. Maybe have some natives as compañeros. But that’s all.

Did you have a Latin American friend, someone you would trust with $1000? Or let him crash at your house aside your wife while you were out of town? Or did you get burned?

I’m writing a book on my time in South America and what I learned. I need your help. I need your experience to bolster mine. You can leave a comment here, email me (colin at expat-chronicles dot com) or post it on the Expat Chronicles subreddit.

I passed this blog post on to three Mexicans, one native-born, two naturalized, and all agreed with your analysis, saying it was absolutely correct. Now, I could pass the same blog post on to newly-landed gringos, and they’d be in shock that anyone could burst their bubble of Kumbaya like that.

LikeLike

Read the chapter about Mexican masks from The Labyrinth of Solitude by Octavio Paz, linked here. Yes, we Mexicans are a friendly, accommodating bunch, but there is more behind those smiles. https://wedgeblade.net/files/archives_assets/13759.pdf

LikeLike

Never lend a Latino anything you wouldn’t give him. Culturally when they say “préstame…” you need to hear “give me”. It doesn’t matter if it’s a hammer, $100, your car or a sweatshirt you will never see it again. I’ve sent long time employees across town with cash in an envelope to make a purchase and claim they were robbed. After 35 years I’ve come to realize that Latinos all have a sense of entitlement. They believe that their foreign benefactor can always get more whereby they are the pobrecito.

LikeLike