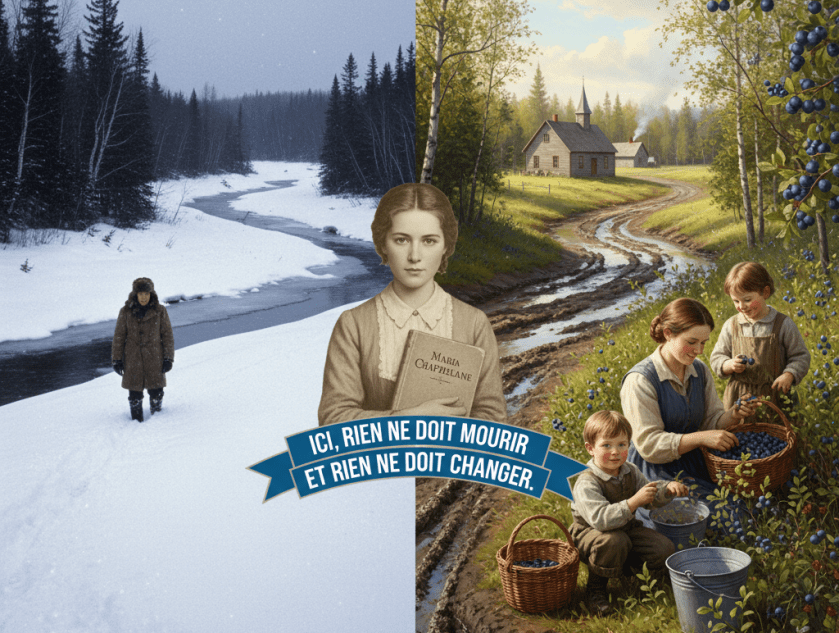

As an old man and overeducated dweeb, I study the history of a place before visiting. Maria Chapdelaine by Louis Hemon was my favorite read on the Quebecois psyche.

The book is so revered that it has been adapted for film four times, most recently in 2021, and they named a municipality after it. It’s like the “Huck Finn” or “Great Gatsby” of Quebec.

The setting is Lac Saint Jean region and the Peribonka River. The book makes you feel how remote, how wild, the area is. These people are pioneers conquering the frontier with logging and subsistence farming. It reminds of Louisiana territory before the Revolutionary War, or Jack London’s Yukon, which is even crazier given the book is set in 1913.

Synopsis: a traditional Quebecois beauty is of age to marry. When her beloved dies, she faces a choice. One is another traditional farmer/logger who will remain in Quebec forever. The other left to work in the factories of Lowell, Mass. He proposes on a visit home to settle his parents’ estate. He promised her all the comforts of 20th century urban life, starting with electricity of course. Maria Chapdelaine refuses to leave her beloved Quebec. She married the farmer.

The setting is a main character in the novel, specifically the harsh winters.

After a few chilly days, June suddenly brought veritable spring weather. A blazing sun warmed field and forest, the lingering patches of snow vanished even in the deep shade of the woods; the Peribonka rose and rose between its rocky banks until the alders and the roots of the nearer spruces were drowned; in the roads the mud was incredibly deep. The Canadian soil rid itself of the last traces of winter with a semblance of mad haste, as though in dread of another winter already on the way.

I had to get my head around that, the grass peeks out from the snow … in June. And the spring bears fruit.

The forests of Quebec are rich in wild berries; cranberries, Indian pears, black currants, sarsaparilla spring up freely in the wake of the great fires, but the blueberry, the bilberry or whortleberry of France, is of all the most abundant and delicious. The gathering of them, from July to September, is an industry for many families who spend the whole day in the woods; strings of children down to the tiniest go swinging their tin pails, empty in the morning, full and heavy by evening. Others only gather the blueberries for their own use, either to make jam or the famous pies national to French Canada.

The setting is both hero and villain. Like Scots or coastal English were often lost as sea, Quebecois could be lost to the forest. SPOILER ALERT: one of the main characters dies on a trek between towns. When traveling during a snowstorm in rural Quebec, you stick to the river. But apparently it can snow so much you lose sight of the river. If you stray from it and get lost, as this character did, you won’t survive the night. You’re dead.

“He went astray…” Those who have passed their lives within the shadow of the Canadian forests know the meaning but too well. The daring youths to whom this evil fortune happens in the woods, who go astray— are lost— but seldom return. Sometimes a search- party finds their bodies in the spring, after the melting of the snows. In Quebec, and above all in the far regions of the north, the very word, écarté, has taken on a new and sinister import, from the peril overhanging him who loses his way, for a short day only, in that limitless forest.

Parish life features prominently in the novel, and learning the links between the Catholic Church and the provincial government well into the 20th century led me to see Quebec as more like Ireland than France.

To go to midnight mass is the natural and strong desire of every French Canadian peasant, even of those living farthest from the settlements. What do they not face to accomplish it! Arctic cold, the woods at night, obliterated roads, great distances do but add to the impressiveness and the mystery. This anniversary of the birth of Jesus is more to them than a mere fixture in the calendar with rites appropriate; it signifies the renewed promise of salvation, an occasion of deep rejoicing, and those gathered in the wooden church are imbued with sincerest fervour, are pervaded with a deep sense of the supernatural.

I mentioned in the first Quebec article that at the Notre Dame de Montreal I saw a group of men take communion on their knees. I had never seen that, not even in Latin America. Given Montreal is melting pot, they may be from Greece or some other orthodox country. But I think they were provincial Quebecois. They all wore beards, jeans and flannels on a hot summer day. Nordiques.

In this next passage, local announcements are read at Mass.

Napoleon Laliberté proceeded in loudest tones:—“ A surveyor from Roberval will be in the parish next week. If anyone wishes his land surveyed before mending his fences for the summer, this is to let him know.” The item was received without interest. Peribonka farmers are not particular about correcting their boundaries to gain or lose a few square feet, since the most enterprising among them have still two-thirds of their grants to clear—endless acres of woodland and swamp to reclaim. He continued:—“ Two men are up here with money to buy furs. If you have any bear, mink, muskrat or fox you will find these men at the store until Wednesday, or you can apply to François Paradis of Mistassini who is with them. They have plenty of money and will pay cash for first- class pelts.”

That shows how wild the country is. Nobody cares about their borders because it’s mostly uncleared … in 1913!

Here the author shows the French fingerprint of personal beauty in the culture.

Meantime the women in their turn had begun to leave the church. Young or old, pretty or ugly, nearly all were well clad in fur cloaks, or in coats of heavy cloth; for, honouring the Sunday mass, sole festival of their lives, they had doffed coarse blouses and homespun petticoats, and a stranger might well have stood amazed to find them habited almost with elegance in this remote spot; still French to their fingertips in the midst of the vast lonely forest and the snow, and as tastefully dressed, these peasant women, as most of the middle-class folk in provincial France.

Like most north country regions, logging is a major industry for the sturdier of men.

The shanties, the drive, these are the two chief heads of the great lumbering industry, even of greater importance for the Province of Quebec than is farming. From October till April the axes never cease falling, while sturdy horses draw the logs over the snow to the banks of the frozen rivers; and, when spring comes, the piles melt one after another into the rising waters and begin their long adventurous journey through the rapids. At every abrupt turn, at every fall, where logs jam and pile, must be found the strong and nimble river-drivers, practised at the dangerous work, at making their way across the floating timber, breaking the jams, aiding with ax and pike- pole the free descent of this moving forest.

This next passage explained a mystery that perplexed me as a child.

When the French Canadian speaks of himself it is invariably and simply as a “Canadian”; whereas for all the other races that followed in his footsteps, and peopled the country across to the Pacific, he keeps the name of origin: English, Irish, Polish, Russian; never admitting for a moment that the children of these, albeit born in the country, have an equal title to be called “Canadians.” Quite naturally, and without thought of offending, he appropriates the name won in the heroic days of his forefathers.

As a child I couldn’t understand why the Montreal Canadiens hockey team could call themselves Canadians, implying the other teams weren’t. An American pro sports club couldn’t get away with calling themselves the “Americans.” Why could Montreal do the same? I figured because they spelled it in French.

But no, this is the root of it… Are you a Smith, Murphy or Kowalski? You’re not a real Canadian! The Tremblays and Roys and Bouchards and Gagnes are the ones who settled this land. The Johnsons and Keanes and the Chinese and the Indians came later, they’re not “real Canadians.”

This next passage could serve as a Quebecois Creed:

Three hundred years ago we came, and we have remained… They who led us hither might return among us without knowing shame or sorrow, for if it be true that we have little learned, most surely nothing is forgot. “We bore oversea our prayers and our songs; they are ever the same. We carried in our bosoms the hearts of the men of our fatherland, brave and merry, easily moved to pity as to laughter, of all human hearts the most human; nor have they changed. We traced the boundaries of a new continent, from Gaspé to Montreal, from St. Jean d’Iberville to Ungava, saying as we did it:— Within these limits all we brought with us, our faith, our tongue, our virtues, our very weaknesses are henceforth hallowed things which no hand may touch, which shall endure to the end. “Strangers have surrounded us whom it is our pleasure to call foreigners; they have taken into their hands most of the rule, they have gathered to themselves much of the wealth; but in this land of Quebec nothing has changed. Nor shall anything change, for we are the pledge of it. Concerning ourselves and our destiny but one duty have we clearly understood: that we should hold fast— should endure. And we have held fast, so that, it may be, many centuries hence the world will look upon us and say:— These people are of a race that knows not how to perish… We are a testimony. “For this is it that we must abide in that Province where our fathers dwelt, living as they have lived, so to obey the unwritten command that once shaped itself in their hearts, that passed to ours, which we in turn must hand on to descendants innumerable:— In this land of Quebec naught shall die and naught shall suffer change…

Considering that passage was written in French is a good segue to Quebec politics. From “History of Quebec” (this book isn’t good, but there isn’t much else specific to Quebec and that’s enough to make money in the self-published era):

Between the 1880s and the 1920s, Quebec’s politics were defined by growing attention to the minority status of the Quebecois within Canada, the enaction of provincial rights, and the role of Quebec’s government in the pursuit to defend Quebec’s linguistic, religious, and cultural traditions. French Canadian resistance to the linguistic and cultural majority of Canadians led to the hardened attitudes of the Quebecois elite toward immigration and the ethnic pluralism that was developing, especially in Montreal. In the post-Confederation era, the Quebec government was caught between two forces: the conflicting interests of conservative Catholicism and maturing industrial capitalists.

The pride illustrated in the novel help explain how difficult politically the Quebecois have been to greater Canada. They have fought tooth and nail to preserve their culture. And while it may not be the most efficient, they have succeeded. Where else is French spoken in North America? The language has lost its integrity in Haiti and is dwindling to nothing in Louisiana. Surrounded by English-speaking capitalists and the hordes of immigrants who follow them around the world, Quebec boasts millions of native speakers and dominates the signage with a language police.

Note: a Frenchman told me Quebecois French can also be difficult to understand.

In the 1960s, the Quiet Revolution maintained the French identity but divorced it from Catholicism and embraced secular liberalism and, in some cases, socialism.

[One] political party and future terrorist group [was] the Front de libération du Quebec (FLQ). The FLQ was committed to overthrowing ‘medieval Catholicism and capitalist oppression’ through revolution. The FLQ held particular resentment toward the federal government and the Anglophone bourgeoisie.

The FLQ were responsible for The October Crisis of 1970, in which the Canadian labor minister and a British diplomat were kidnapped. The group killed the labor minister when he tried to escape.

That episode led to a backlash against extremism, but Quebec nationalists managed to put forward an independence referendum in 1995, which narrowly failed. In provincial Quebec, I saw at least 10 flags of Quebec for every Canadian red and white. And a bumper sticker that read “Libres Chez Nous.”

Quebecker novelist Hubert Aquin explored violent extremism and espionage in “Next Episode,” which I read but was disappointed. It wasn’t even set in Quebec, but Switzerland. However his frequent descriptions of the countrysides, the chateaus, the cafes and the meals reinforced my view of the French focus on beauty.

The main political issue that comes across to overly informed Americans is Quebeckers generally contributing the least to the national budget and extract the most. Meanwhile, they often oppose the oil and gas infrastructure that pays Canada’s bills.

So from a rational, logical standpoint, the good gringo inside should have a little contempt for Quebec. But the old man who is ready for cleaner, safer, more civilized with a heavy dose of beauty, and the excitement of the strange and the new with a new language (and music), this old man is still very curious about Quebec.